Thoughts from a Darkened Corner: Sustainability Education in Times of Crisis

Summary

To those concerned for the wellbeing of people and planet, education for sustainable development seems a positive way forward. But the warm, fuzzy feeling it engenders masks a shying away from a range of issues that have to be addressed if the intention is to realize a sustainable future. Education for sustainable development fails to confront the dire threat posed to environments and societies by unrestrained economic growth just as it sidesteps a fundamental critique of the neoliberal project of turning the planet into a global marketplace. The common assumption that the environmental, economic and social dimensions of sustainability are complementary, achievable states needs unpacking. They are only so if we move away from a growth mindset. Schools should become seedbeds for learning about and living alternative no growth forms of economy. Education for sustainable development enshrines a prevailing human-centeredness that sees nature as something to be used and exploited. An ethic of oneness and intimacy with nature is needed so nature is intrinsically valued and so that people fight to hold onto something they love. The prevailing rationalism of education for sustainable development needs to be tempered with, even replaced by, the cultivation of the ability to relate to life through nature intimacy. Education for sustainable development takes a ‘business as usual’ approach to climate change, failing to address the profound challenge to the world as we know it, the denial and loss that is increasingly involved, the threat posed by rampant consumerism, and climate injustice. Education for sustainable contraction and education for sustainable moderation might be more appropriate terms given the profound crisis of unsustainability we face.

Μετάφραση Περίληψης

Για όσους ενδιαφέρονται για την ευημερία των ανθρώπων και του πλανήτη, η εκπαίδευση για τη βιώσιμη ανάπτυξη φαίνεται να είναι ένα θετικό βήμα προς τα εμπρός. Αλλά, το ζεστό, φλου συναίσθημα που προκαλεί, καλύπτει μία άρνηση αντιμετώπισης μιας σειράς ζητημάτων που πρέπει να αντιμετωπιστούν, εάν η πρόθεσή μας είναι η δημιουργία ενός αειφόρου μέλλοντος. Η εκπαίδευση για τη βιώσιμη ανάπτυξη αποτυγχάνει να αντιμετωπίσει την έσχατη απειλή που έχει δημιουργηθεί στα περιβάλλοντα και στις κοινωνίες μέσω της ανεξέλεγκτης οικονομικής μεγέθυνσης, με τον ίδιο τρόπο που αποφεύγει τη βασική κριτική του νεοφιλελεύθερου προγράμματος, που έχει ως στόχο να μετατρέψει τον πλανήτη σε μία παγκόσμια αγορά. Η κοινή παραδοχή ότι οι περιβαλλοντικές, κοινωνικές και οικονομικές διαστάσεις της αειφορίας είναι συμπληρωματικές, χρειάζεται να διερευνηθεί, γιατί το εάν αυτό είναι εφικτό δεν είναι δεδομένο. Είναι συμπληρωματικές μόνο εάν απομακρυνθούμε από ένα τρόπο σκέψης που σχετίζεται με τη μεγέθυνση. Τα σχολεία πρέπει να γίνουν τα σπορεία για μάθηση και για ένα τρόπο ζωής σε εναλλακτικές μορφές οικονομίας χωρίς μεγέθυνση. Η εκπαίδευση για τη βιώσιμη ανάπτυξη κρύβει ευλαβικά μία κυρίαρχη ανθρωποκεντρικότητα που βλέπει τη φύση ως κάτι χρησιμοποιήσιμο και εκμεταλλεύσιμο. Χρειάζεται μία ηθική της αίσθησης ότι είμαστε ένα και της οικειότητας με τη φύση, έτσι ώστε να δίνεται στη φύση εγγενής αξία και οι άνθρωποι να παλεύουν να διατηρήσουν κάτι που αγαπούν. Ο κυρίαρχος ορθολογισμός της εκπαίδευσης για τη βιώσιμη ανάπτυξη χρειάζεται να μειωθεί με, ή ακόμη να αντικατασταθεί από, την καλλιέργεια της ικανότητας να σχετίζεται με τη ζωή μέσω της οικειότητας με τη φύση. Η εκπαίδευση για τη βιώσιμη ανάπτυξη ακολουθεί μία προσέγγιση στην κλιματική αλλαγή του «μία από τα ίδια», αποτυγχάνοντας να αντιμετωπίσει τη βαθιά πρόκληση προς τον κόσμο όπως τον ξέρουμε, την άρνηση και την απώλεια που συνεχώς αυξάνονται, την απειλή που δημιουργεί ο αχαλίνωτος καταναλωτισμός και την αδικία την σχετική με το κλίμα. Η εκπαίδευση για την αειφόρο συρρίκνωση και η εκπαίδευση για τον αειφόρο μετριασμό, είναι ίσως καταλληλότεροι όροι, δεδομένης της βαθιάς κρίσης της μη αειφορίας που αντιμετωπίζουμε.

(Μετάφραση Βέτα Τσαλίκη)

From the perspective of someone concerned about the wellbeing of people and planet, educating for sustainable development (ESD) looks a very good idea. Who, from such a perspective, would not be warmed by UNESCO’s rendition of the underlying values of ESD?

- Respect for the dignity and human rights of all people and a commitment to social and economic justice

- Respect for the human rights of future generations and a commitment to intergenerational responsibility

- Respect for the greater community of life in all its diversity (protecting and restoring the Earth’s ecosystems)

- Respect for cultural diversity and a commitment, locally and globally, to a culture of tolerance, non-violence and peace (UNESCO, 2004,14).

Again, who of a concerned humanistic disposition would not be cheeredby a summary list of the key characteristics of ESD?

- Deals with all three realms of sustainability – environment, society and economy

- Promotes lifelong learning

- Is locally relevant and culturally appropriate

- Is based on local needs, perceptions and conditions, but acknowledges internationaleffects and consequences

- Engages formal, non-formal and informal education

- Builds civil capacity for community-based decision-making, social tolerance, environmental stewardship, an adaptable workforce, and quality of life

- Is interdisciplinary in that no single discipline can claim ESD for itself

- Uses a variety of pedagogical techniques that promote participatory learning and higher-order thinking skills(UNESCO/UNEP, 2011, 56).

Such statements of values and key characteristics are the product of mounting concern about the unsustainable state of the contemporary world; a conviction that we cannot continue as we are without facing a dire future. They seek to align education with the original sustainable development (SD) definition of 25 years ago: ‘Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs’ (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987, 43).

At the same time such statements have the warm, fuzzy feel that often marks outcomes of compromise. At the global level, sustainable development has been a means of papering over the cracks between the environmental lobby, on the one hand, and the development lobby on the other. Definitions were left vague enough to allow everyone to invest terms such as ESD with their own meaning. They were left attractively uncontroversial and unexceptional enough, too, to enable ESD advocates at local level to achieve at least some leverage and influence within mainstream, conservatively inclined educational systems that were unlikely to concretely take on board the full implications of sustainability (Selby, 2006, 352-4).

But this has left environmental and social justice educators groping around like the person looking for the lost key in the Sufi story:

He was found to be looking for it under a light. He looked and looked and couldn't find it. Finally, someone asked where he had lost it. He answered, “Well, I did in fact lose it over there.” And when asked why he didn’t look for it over there, he said, “Well. It’s dark over there, but there is light here for me to look” (Bohm & Edwards, 1991, 17).

We face a growing confluence of environmental, economic, social and cultural crises yet our ESD tends to stay within the comfortable arc of light of ‘business as usual’where we can easily deceive ourselves into thinking we will find the key to a sustainable future.

But what do we see if we look in the darkened, unexplored corner?

We find, for a start, the ubiquitous but largely unheeded issue of economic growth –the ESD field has more or less failed to confront the dire threat that economic growth poses to sustainability

Right from the start this has been a problem. The World Commission on Environment and Development of 1987 saw economic growth and sustainable development as largely harmonious concepts, a view compounded at the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (Gutierrez Perez &PozoLorente, 2005, 298). SD and ESD stakeholders have, for the most part, taken the same view or avoided the issue, explicitly or implicitly falling in with the idea that ‘development’ means ‘growth’. As such, the field colludes with what has been called ‘growth fetishism’:

In affluent societies…religious value seems to be invested in the most profane object, growth of the economy, which at the individual level takes the form of accumulation of material goods. Our political leaders and commentators believe it has magical powers that provide the answer to every problem. Growth alone will save the poor. If inequality causes concern, a rising tide lifts all boats. Growth will solve unemployment. If we want better schools and more hospitals then economic growth will provide. And if the environment is in decline then higher growth will generate the means to fix it. Whatever the social problem, the answer is always more growth (Hamilton, 2010, 33).

This ‘no alternative to growth’ perception is deeply embedded in society, including our educational systems. Indeed, continued economic growth has taken on delusionary proportions. There is ‘irrational insistence on endless growth as a non-negotiable axiom by a large proportion of the world’s population’ (Lloyd, 2009, 517). Those with the temerity to question growth are ‘denigrated as aberrant spoilsports’ (ibid) and characterized as ‘opponents of progress’ wishing us back to a cave dwelling existence (Hamilton, 2010, 34). Viable alternatives are not there to countenance; they are banished from the mainstream landscape (Fisher, 2009).

Yet, there is abundant evidence that growth – as it subjugates the planet to the demands of the global marketplace – is greedily eating up ecosystems, cultures and communities and is the underlying driver of climate change (Hamilton, 2010; Hossay, 2006; Woodward & Simms, 2006). These linkages are but rarely being made by sustainability educators – for the very reason, I suspect, that to make them would mean that they would have even less influence in a mainstream education system imbued with the growth ethic. Rather, there is a tendency to self-censor to maintain some influence.

A critical thought from the dark corner follows: Are we preparing students for life on a planet or life in a growth-oriented global marketplace?

A recent 2011 meta-survey of European ESD programs reveals barely any topics being taught that scrutinize growth and its culpability for fuelling the multi-facetted global crisis we face (Selby & Kagawa, 2011).

In the ESD field the idea that globalization and sustainability go together seems to be widely embraced as a wholly unexceptional idea - that an increasingly globalized world is a viable platform for realizing a sustainable and just future. This is seen most starkly in courses that bring together sustainability and globalization themes and focus on skills development for competitive positioning in the global marketplace (see, for instance, Bourn, 2009).

The field has more or less suppressed the status-quo critical nature of much environmentalism – as these Latin American educators suggest:

ESD discourse has contributed quite successfully to diluting and blurring all the work of sensitization, consciousness-raising and denunciation that has been constructed by pro-environmental social movements in recent decades and more recently by environmental education (Guttierez Perez and PozoLorente, 2005, 298).

And yet, the ‘globalization from above’ (Torres, 2009, 14) that is happening through the workings of the world marketplace is inexorably undermining the sustainability of cultures, peoples and environments around the world.

A counter movement of ‘globalization from below’ (ibid. 15) is made up of the myriad more or less interconnected expressions globally of social and environmental justice activism and indigenous cultural resistance; what has been described as the phenomenon of ‘blessed unrest’; the grassroots stirring of people defending the ‘timeless ways of being human now threatened by global forces that do not consider people’s deepest longings’ (Hawken, 2007, 15).

This prompts a second thought from the darkened corner: Does our sustainability education uncritically accept ‘globalization from above’ or does it give prominence to understanding and cultivating the ‘blessed unrest’ of ‘globalization from below’?

From the darkened corner - and building on what has been said about economic growth and globalization – we find that questions also need to be asked of the common assumption that different dimensions of sustainability – environmental, economic and societal – stand in comfortable co-existence. The three – sometimes called the ‘triple bottom line’ (cultural being merged with social) – are largely seen as complementary, achievable states. This is open to question if sustainable development is taken to mean sustainable growth (expressing itself at the individual level as rampant consumerism). Both the ecosphere (the environmental dimension) and the ethno-sphere (the social and cultural dimensions) are unsustainable in the face of unrestricted growth:

Comparing the sustaining of ecological processes with the sustaining of consumerism reveals inconsistencies and incompatibilities of values, yet many people, conditioned to think that sustainable development is inherently good, will promote both at the same time (Jickling & Wals, 2008, 14).

This leads to a third thought from the darkened corner – the place where too few look: The different dimensions of sustainability are only collectively attainable if economic sustainability is expressed through no growth or steady state economies (i.e. where patterns of consumption stay at or below nature’s carrying capacity) or ‘gift’ economies (i.e. where gift exchanges redistribute wealth through a community). Schools should give students understanding and localized experience of developing and using alternative (green) forms of economy.

Other thoughts from the darkened corner concern the prevailing human-centeredness of Education for Sustainable Development. Its discourse suggests a predominantly instrumental, utilitarian and exploitative view of nature (nature being described as ‘resource’, ‘natural capital’, ‘ecosystem services’). Conceiving nature in such a way denies the deep ecological perspective that ecosystems and the other-than-human entities possess intrinsic value (value in their own right). It is counter-productive in building students’ intimate engagement with and sense of being embedded in nature. It stands in the way of cultivating poetic intimacy with nature. Missing from the lexicon of ESD are words like attunement, awe, beauty, celebration, enchantment, enfoldment, intuition, magic, reverence, wonder. In short, much ESD compounds the ongoing estrangement of humanity from nature.

Intimacy with nature is crucial in fomenting ‘blessed unrest’. That intimacy walks the line between science and spirituality as it cultivates resistance to forces destroying cultural and natural environments. In a time of violation of flora and peoples occasioned by the English land enclosures and agricultural modernization of the 1820s, the laborer poet John Clare conveyed a sense of loss through finely-detailed depiction of flower species under threat, images that in their detail also betokened a sense of oneness between flora, fauna and laborers ‘as fellow members of the great commonwealth of the fields,’ now sharing a common fate in their eviction (Mabey, 2010, 115-26). Clare’s radicalism was bred of nature intimacy in which were folded together science, spirituality and social justice. Similarly, today it is profoundly important in the face of environmental crisis to enable learners to cultivate a sense of oneness with nature through scientific intimacy and poetic and spiritual ways of knowing (Selby & Kagawa, 2011b, 7). To borrow the title of Eban Goodstein’s fine book (2007) we are:Fighting for Love in the Century of Extinction.

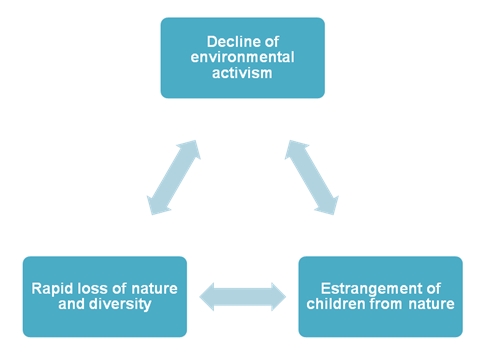

The above diagram captures the argument put by Monbiot (2012a, 30) that we are facing ‘a second environmental crisis: the removal of children from the natural world’. Story after story about climate change and loss of biodiversity assail us with insistent frequency. But ‘where,’ he asks, ‘are the marches, the occupations, the urgent demands for change?’ The problem, he responds, is that ‘the young people we might have expected to lead the defense of nature have less and less to do with it.’ He proceeds to enumerate examples illustrative of the ‘remarkable collapse of children’s engagement with nature – which is even faster than the collapse of the natural world’. For instance:

- Since the 1970s the area in which children can roam without supervision has decreased by almost 90%

- In one generation the proportion of children playing regularly in the wild has fallen from more than half to fewer than one in 10

- In the USA in just six years (1997-2003), children with outdoor hobbies fell by half.

There are myriad factors behind such trends – for instance, safety fears on the part of parents, destruction of common outdoor areas for play, the quality of indoor entertainment. The decline of outdoor experience matters for the environment in that ‘if children lose contact with nature they won’t fight for it.’ Estrangement from nature thus fuels environmental destruction. ‘Most of those who fight for nature are people who spent their childhood immersed in it. Without a feel for the texture and function of the natural world, without an intensity of engagement almost impossible in the absence of early experience, people will not devote their lives to its protection (ibid.).

The urgent need to address dissociation of sensibility – the breaking up of the ability to feel and richly relate to life through nature connection (McIntosh, 2008, 154) - prompts a further thought from the darkened corner: The overriding rationalism of education for sustainable development needs serious redress in that rationality is too blunt and limited a tool for solving issues as complex, subtle and multidimensional (weaving the solid and the impalpable) as environmental concern. In fact, rationality has proved altogether very effective in exploiting the environment.

Let us turn to climate change. Climate change is unequivocally happening and the future looks grim. Should carbon emissions are not significantly reduced, those living in a climate-changed future will increasingly experience:

- Ubiquitous environmental disaster, including the ‘slow onset’ disaster of biodiversity loss

- Massive internal and external population displacement as rising sea levels swallow the land and as aridification and seasonally recurring wildfires make land inhospitable

- Resultant social dislocation

- Loss of food security (hunger and malnutrition)

- Strife, violent conflict, tribalism

- Aggressively defensive localism

The ‘storms of our grandchildren’ (Hansen, 2009) in both a concrete and metaphorical sense will indeed be frequent and catastrophic.

Not that the present is short of trauma and tragedy. A report from the Global Humanitarian Forum (2009) describes the ‘silent crisis’ of climate change that is already upon us and that, on yearly average, is causing over 300,000 deaths, seriously affecting 325 million people and bringing about losses of US$125 billion per year.

ESD advocates have, indeed, responded to climate change, often claiming it as an issue very much falling within their province. For instance:

The obvious answer is to treat CCE (climate change education) as ESD. …CCE (climate change education) should be formally integrated within ESD, where it has great potential as a focal theme for the next decade. (International Alliance of Leading Educational Institutes, 2009).

But there are serious questions to be asked about locating climate change learning within an ESD framework that remains more or less characterized by an uncritical approach to growth, globalization and the prevailing human-nature relationship, all of which, my argument goes, are stoking the heating of the planet.

ESD, I would suggest, has not shaken off the myths we tell ourselves, myths repeated so often we take them as truth beyond reasonable doubt:

- The myth of unending growth

- The myth of continually upward progress

- The myth of human centrality to existence

- The myth of separation from and dominion over nature

Against the backcloth of these largely unquestioned myths, mainstream ESD treatment of climate change is marked by a number of key characteristics:

- Climate change is largely conveyed as a technical problem to be primarily managed through technological innovation and policy solutions

- Climate change is a crisis to be addressed through a ‘business as usual’ lens in which ‘green’ development is encouraged

- There is avoidance of the notion that we live in a time of fundamental social, ecological and economic unraveling that can only become more acute

- There is reluctance to address the culpability of neo-liberal growth models for fomenting climate change

- There is a failure to address the issue of consumerism in any critical, root-and-branch way

- There is avoidance of examining personal and societal scenarios likely to be played out in the learner’s lifetime

- The ubiquitous presence of climate change denial is not addressed

- There is avoidance of coming to terms with loss of what we value

- There is a blind spot with respect to global climate change injustice.

Let us look at climate change denial and loss, consumerism and climate injustice.

Denial and Loss

A thought from the darkened corner: Given that the climate crisis is already upon us, and given that we face the looming prospect ofthe crisis deepening still further, silently and slowly but also abruptly and fickly, education for climate change needs to confront denial and also address despair, pain, grief and loss.

Let us first address denial by looking at 28 August 2012. On that day:

- Scientists announced a record summer Arctic ice-melt, a clear indication that global heating is happening even faster than had been expected. The announcement barely made the news.

- On that day, British newspapers headlined the controversy over where the third London airport should be built (with no discussion of whether it should be built at all)

- In the US the Republican Party Convention began a day late in Tampa, Florida because of the severity of Hurricane Isaac but speaker after speaker stood up to deny the validity of climate change. (Monbiot, 2012b)

Denial is everywhere. There is ‘a near universal state of denial, close to collective amnesia, about the significance of climate change’, an ‘eyes wide shut’ syndrome (Hillman et al, 2007, 85). It is of vital importance that climate change denial is confronted through sustainability (and environmental) education, and that students becoming denial-critical, i.e. skilled up so they can detect, name and handle avoidance and denial.

Despair also needs to be addressed. It is a fallacy, perhaps born of western absorption with the idea of progress, that ‘gloom and doom’ thinking is widely held to be disabling and disempowering. On the contrary, working through despair can be a powerful progenitor of new vision and commitment. ‘We are compelled,’ writes O’Murchu (2004, 192-3), ‘to assert what seems initially to be an outrageous claim: a radical new future demands the destruction and death of the old reality. It is from the dying seeds that new life sprouts forth. Destruction becomes a precondition for reconstruction.’ Truly transformative learning, then, requires a conscious and thoroughgoing progress through despair, into empowerment with healing and renewal. The ‘Great Turning’, as Macy & Young-Brown (1998, 17-22) call it, involves breaking through denial to confront the pain of the world, heroic holding actions to stop things getting worse, analysis of the structural causes of the damage wreaked by the ‘Industrial Growth Society’, allied to the nurturing of alternative institutions and, most fundamental of all, a cognitive and affective, perceptual and spiritual awakening to the wholeness of everything. We need to use approaches like Joanna Macy’s despair and empowerment activities that take leaners through despair and loss, to new commitment, hope and purpose (Macy, 1983, 1991).

To look only where the comfortable light shines leads to the easy embrace of inauthentic hope, no real platform for the future. To work through the darkness can build a realistic, grounded, authentic hopefulness. ‘We cannot address the future in a serious and comprehensive way without embracing the dark and perilous threat that hangs over us as a human and planetary species’ (O’Murchu. 2004, 192)

My organization, Sustainability Frontiers, is working on disaster risk reduction education aimed at having children and communities confront threats and build the mindset and skills of resilience to both adapt to and mitigate threat. Having learners visualize negative futures and then work through how to prevent them from actually happening is an important strategy.

Consumerism

Staying within the comfortable arc of light that is ‘business as usual’, ESD programs also tend to sidestep root and branch scrutiny of consumerism defined by McIntosh (2008, 180) as ‘consumption beyond the level of dignified sufficiency’. Fuelled by the advertising industry and its dream factory of images and desires, consumerism has become key to personal identity for millions and millions of people. What we buy shapes how we feel about ourselves. To borrow from Descartes, ‘I consume, therefore I am’. But the substitute gratification we enjoy is not authentic identity and the ‘I am’ requires regular purchasing replenishment. A ‘constant feeling of dissatisfaction to sustain spending’ is essential in the global marketplace because ‘unhappiness sustains economic growth’ (Hamilton, 2010, 71).

Another thought, then, from the darkened corner: We need to address consumerism head on in our sustainability and environmental programs, going beyond ‘consumerism awareness education’ (with its subliminal agenda that consumerism can be made benign) to ‘anti-consumerism education’ (where learners deconstruct the economic, environmental and identity-distorting effects of consumerism while examining, envisioning and practicing alternative versions and visions of the ‘good life’).

Climate Injustice

Issues of climate justice and injustice are rarely feature in ESD curriculum programs in countries of the affluent North of the planet. They should do.While countries in the South of the planet are held to account for their financial indebtedness, there is no holding to account for their ecological indebtedness arising from their polluting of the global atmospheric commons. Also the effects of climate change are falling in a hugely disproportionate way on nations and communities of the South, who are least responsible for CO2 emissions.

A penultimate thought from the darkened corner follows: Sustainability programs need to initiate cosmopolitan North-South dialog on climate injustice and how climate change is impacting on sustainability. As climate change bites harder, in-country, regional and global sharing of experiences, perspectives, problems and success stories will become increasingly important. Global solidarity building – a sharing of blessed unrest – is going to be very important as we seek to effect transformative change for future resilience.

Conclusion

So, in summary, I am saying that mainstream sustainability education is much too closely caught up in a ‘business as usual’ agenda, and is more or less restricted to reforming or moderating the effects of unsustainable patterns and ways of living rather than seeking the root-and-branch transformation that our global condition calls for. There is, I would suggest, no space or place for the diversionary when what we are facing is a ‘race between learning and the possibility of self-destruction’(Wenger, 2006, 1)

This prompts a final dark corner thought: Should we take ‘development’ out of the equation, given what it has come to connote, and work within a frame of education for sustainable contraction, a learning approach seeking to slow down or reverse current trends with the ultimate aim, when a steady state is achieved, of it segueing into education for sustainable moderation?

References

Bohm, D. and Edwards, M. (1991). Changing Consciousness: Exploring the Hidden Source of the Social, Political and Environmental Crises Facing Our World. San Francisco: Harper.

Bourn, D. (2009). Globalization and sustainability: The challenges for education. Environmental Scientist, 18(1), 12-14, 52.

Fisher, M. (2009). Capitalist Realism: Is there no alternative? Winchester (UK): O Books.

Global Humanitarian Forum. (2009). The Anatomy of a Silent Crisis.Geneva: Global Humanitarian Forum Impact Report 1.

Goodstein, E. (2007). Fighting for Love in a Century of Extinction: How Passion and Politics Can Stop Global Warming. Lebanon NH: University of Vermont Press.

Gutierrez Perez, J &PozoLorente, M.T. StultiferaNavis: Institutional tensions, conceptual chaos, and professional uncertainty at the beginning of the Decade of Education for Sustainable Development. Policy Futures in Education, 3(3), 296-308.

Hamilton, C. (2010). Requiem for a Species: Why We Resist the Truth about Climate Change. London: Earthscan.

Hansen, J. (2009). Storms of My Grandchildren: The Truth about the Coming Climate Catastrophe and Our Last Chance to Save Humanity. London: Bloomsbury.

Hawken, P. (2007). Blessed Unrest: How the Largest Movement in the World Came into Being and Why No One Saw it Coming. London: Viking.

Hillman, M., Fawcett, T. &Rajan, S.C. (2007). Suicidal Planet.New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Hossay, P. (2006). Unsustainable: A Primer for Global Environmental and Social Justice. London: Zed Books.

International Alliance of Leading Educational Institutes. (2009). Climate Change and Sustainable Education: The Response from Education. Copenhagen: International Alliance of Leading Educational Institutes.

Jickling, B. &Wals, A. (2008). Globalization and environmental education: looking beyond sustainable development. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 22(1), 99-104.

Kagawa, F. & Selby, D. (2011a). Development education and education for sustainable development: Are they striking a Faustian bargain? Policy & Practice, 12, 15-31.http://www.developmenteducationreview.com/issue12

Kagawa, F. & Selby, D. (2011b). Unleashing blessed unrest as the heating happens. Green Teacher, 94, 3-15.

Lloyd, B. (2009). The growth delusion.Sustainability, 1, 516-36.

Mabey, R. (2010). Weeds: How Vagabond Plants Gatecrashed Civilization and Changed the Way We Think about Nature. London: Profile.

Macy, J. (1983). Despair and Personal Power in the Nuclear Age.Philadelphia: New Society.

Macy, J. (1991). World as Lover, World as Self.Berkeley (CA): Parallex.

Macy, J. & Young-Brown, M. (1998). Coming Back to Life: Practices to Reconnect Our Lives, Our World. Gabriola Island (BC): New Society.

McIntosh, A. (2008). Hell and High Water: Climate Change, Hope and the Human Condition. Edinburgh: Birlinn.

Monbiot, G. (2012a). If children lose contact with nature they won’t fight for it. The Guardian, 20 November 2012, 30.

Monbiot, G. (2012b). The day the world went mad. Guardian blog.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/georgemonbiot/2012/aug/29/day-world-went-mad

O’Murchu, D. (2004). Quantum Theology: Spiritual Implications of the New Physics. New York: Crossroad.

Selby, D.E. (2006). The firm and shaky ground of education for sustainable development.Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 30(2), 351-65.

Torres, C. Education and Neoliberal Globalization.New York: Routledge.

UNESCO. (2004). United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development 2005-2014: Draft International Implementation Scheme. Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO/UNEP. (2011). Climate Change Starter’s Guidebook.Paris/Milan: UNESCO/UNEP.

Wenger, E. (2006). Learning for a Small Planet: A Research Agenda. September. http://www.ewenger.com/research/index.htm

Woodward, D. & Simms, A. (2006). Growth isn’t Working: The Uneven Distribution of Benefits and Costs from Economic Growth. London: New Economics Foundation.

World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987). Our Common Future.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Η πλήρης μετάφραση στα Ελληνικά της προσκεκλημένης ομιλίας του David Selby είναι δημοσιευμένη στο τεύχος 4(49)

The author

David Selby is Founding Director of Sustainability Frontiers, a not-for-profit organization with offices in Canada and the United Kingdom. He works in the fields of climate change education, disaster risk reduction education and education for sustainability. He co-edited, with Fumiyo Kagawa, Education and Climate Change: Living and Learning in Interesting Times (Routledge, New York, 2010), the first comprehensive academic treatment of climate change education. His upcoming book, again co-edited with Fumiyo Kagawa, is Transformative Voices from the Borderlands of Sustainability Education (Barbara Budrich, 2013). He has acted as a consultant on climate change education and disaster risk reduction education for UNESCO, UNICEF, Plan International and Save the Children, his most recent publication being Disaster Risk Reduction in School Curricula: Case Studies from Thirty Countries (UNESCO/UNICEF, 2012). The sequel, Towards a Learning Culture of Safety and Resilience: Technical Guidance on DRR in School Curricula will be published in 2013. Both these publications are co-authored with Fumiyo Kagawa. For more on Sustainability Frontiers and its projects and publications, please visit: http://www.sustainabilityfrontiers.org

Copyright © 2012 Πανελλήνια Ένωση Εκπαιδευτικών για την Περιβαλλοντική Εκπαίδευση

Copyright © 2012 Πανελλήνια Ένωση Εκπαιδευτικών για την Περιβαλλοντική Εκπαίδευση